A Legacy: Building A Bridge of Lives

Building bridges, that is establishing true connections between two people can result in life-changing consequences.

We were on the eve of the new millennium: 1999, a time of both great possibility and equally great foreboding. Remember the threat of the dreaded Millennium Bug?

As the structures of my own world, many of them built in Hong Kong and imported back to Ireland, crashed down around my ears and I was faced with having to pull down the shutters on Arts & Noise, my event management business, I was thrown one last straw that might save me from drowning.

While my strange hybrid of a CV from Hong Kong – Senior Inspector of Police by day, arts & events promoter by night – made little sense to almost no-one I showed it to, one person saw through the confusion and recognised what I might do for them and their project.

Cartan Finegan, the man who had dreamed up and delivered the Dart rail project to Dublin in the 80s, was now Chairman of the National Safety Council, a body with responsibility for road safety.

The previous October, at that time of year when the days grow darker and wetter, and the roads are at their most treacherous, Senator Fergal Quinn, he of Superquinn fame, had stood and berated his fellow senators, and by extension the people of Ireland, on what he described as the national tragedy and disgrace of the more than 450 people who died on our roads every year. And the many thousands more whose lives were wrecked by catastrophic injury. And he called for a national road safety campaign over the October 1999 Bank Holiday weekend, which typically marked the beginning of the most perilous period of time to be on the road – November through February.

And it fell to Cartan Finegan to commission this life-saving campaign. And where others saw a bewildering mess of a CV, Cartan saw in me someone whose experience as a police officer combined with my event management skills might design and deliver such a campaign, and he invited me to head up a small project team working directly under him.

While I had never before dealt with a project quite like this one, I got to work on it in the only way I knew, from the only starting point that was familiar to me. Just as I had stood in the empty space of my art gallery in Hong Kong every three to four weeks as I planned our next exhibition and tried to picture both the art that would soon hang on its walls and the visitors who might buy it, I visited some of the more notorious road accident black spots around the country, many of them in isolated, rural areas, and stood and remembered those who had killed and who had died there, and I tried to picture them and the series of events that had led to the carnage.

And while others used the term road-accident to describe what had happened, I saw no accident, only design. There is no accident involved when two young men in separate parts of a county, each the mirror image of the other, get behind the steering wheel of a car, both fired up on youthful spirits and alcohol and with the encouragement of their equally-fired up passengers, and race headlong across the countryside towards one another and almost certain death and mutual destruction.

When two people tragically encounter one another in this way, form a relationship in this way, then death or catastrophic injury is not by accident but rather by deadly design.

And so I resolved to design a campaign that would acknowledge the parts played by both the killer and their victim, the buyers and sellers of slaughter, those about to form a fatal relationship, and call for the two to take a very different course of action.

And as I stood on the blind corner of a country road, I pictured the two assailants hurtling towards one another in this way, the images conjured up in my mind those old stories of the knights on horseback, each holding a deadly lance, racing towards each other for sport, intent on annihilating their opponent.

And I remembered that when a medieval knight on the road wished to signal that he intended no harm to others approaching him from the far side, he would wear a white kerchief on the wrist of his sword-hand, the precursor of the white flag of surrender.

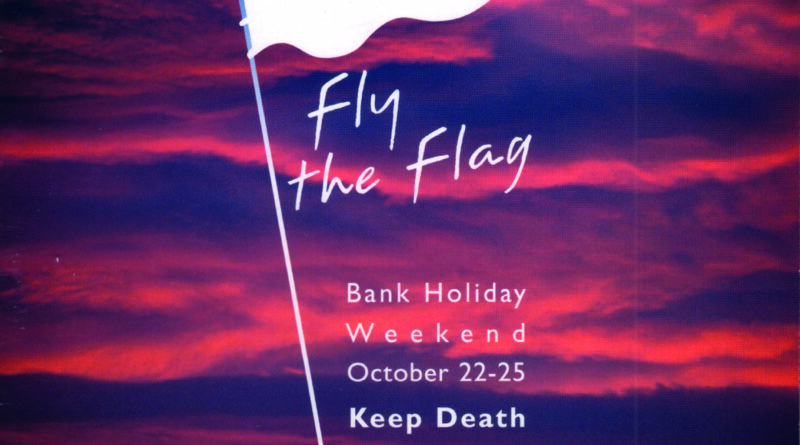

And so our Fly The Flag campaign was born. Over the October Bank Holiday weekend in 1999, on the eve of millennium, we invited motorists and other road users to display a white pennant on their vehicle or on their clothing to say to others: I will do you no harm.

This weekend, I will do you no harm. I will not drink and drive. I will not drive faster than safe speed. This weekend, I will keep us all safe on the road.

The impact of our campaign was staggering, almost miraculous. Reframing the relationship between those who are most likely to kill and to die on the roads, those young heroes in remote country towns and villages, as a bond made between two noblemen, two men of honour – ‘I will do you no harm’ – resulted in a reduction of more than 40% in the numbers of road deaths in the four months that followed.

And set in motion a series of campaigns over the decades that followed which saw road deaths fall from over 450 each year to as low as 150 in more recent times. That’s still one hundred and fifty too many, but far fewer than the many thousands of lives that would have been lost, and the tens of thousands more devastated, if we hadn’t chosen to build a safe relationship by design, rather than an unsafe one by accident.

This article is Gerard’s submission to CongRegation (the unconference) 2024.